Americans are rightly anxious about the increasing prevalence of serious and deadly infections associated with drug-resistant pathogens – also known as antimicrobial resistance (AMR). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is currently investigating several alarming and rising AMR threats that have gripped the attention of health experts, the media, and the public in 2023 alone.

Top federal officials are warning of a steep rise in severe stomach illnesses caused by a drug-resistant strain of the bacteria known as Shigella. Cases of the fungal superbug Candida auris tripled over the last three years, according to a new study. There has also been a string of deaths and gruesome injuries linked to eye drops contaminated with drug-resistant bacteria.

These recent outbreaks are all connected to the worrying phenomenon of AMR.

What is AMR?

AMR refers to the evolution of bacterial and fungal pathogens to adapt and develop immunity to existing antimicrobials and other treatments. The rise of AMR is rapidly rendering our arsenal of medicines ineffective, posing a grave danger to everyone – today.

The AMR crisis intensified during the pandemic as hospitals filled up with patients fighting COVID-19. The pandemic significantly impacted the progress our healthcare system was making to address AMR. According to a CDC report, deaths from hospital-onset superbugs increased by an average of 15% in 2020 alone, with certain resistant infections experiencing rises of over 70%, compared to decreases in previous years. This reversed progress made in 2012-2017 to lower U.S. deaths from AMR.

COVID-19 undoubtedly catalyzed a spike in drug-resistant infections, but the silent pandemic of “superbugs” has been building for decades. Though antimicrobials have saved millions of lives since their discovery in the mid-twentieth century, the overuse and misuse of these critical medicines have also accelerated AMR, as pathogens continuously evolve into strains that resist the therapies designed to address them.

We’re unprepared to combat superbugs

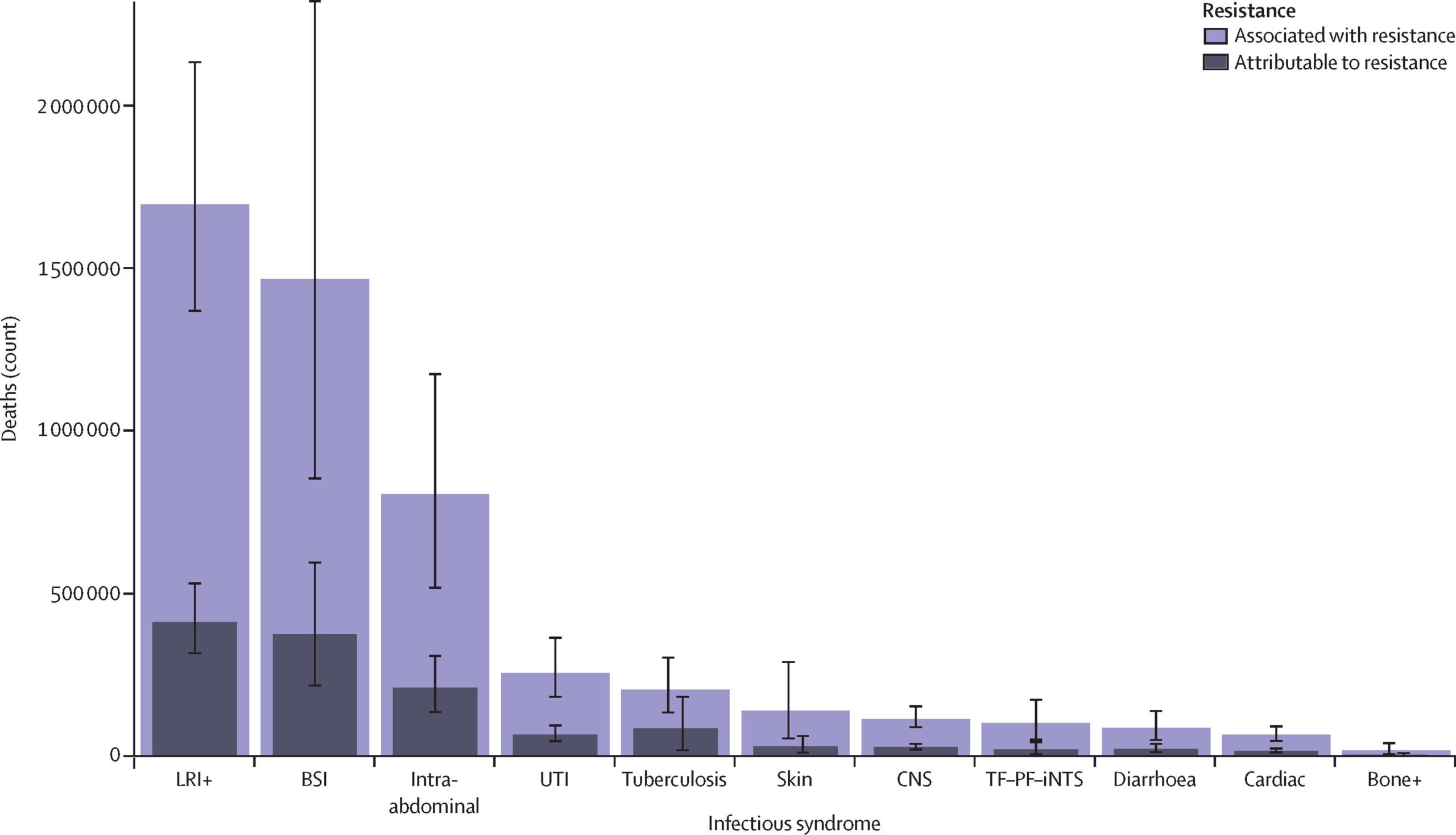

Superbugs were linked to almost 5 million deaths worldwide in 2019, making AMR a leading cause of mortality worldwide. Even before COVID-19, AMR was on the CDC’s list of “greatest public health concerns.” According to pre-pandemic estimates, in addition to the toll on human life, superbugs cost the U.S. $55 billion every year, and the problem is only getting worse.

We are currently unprepared to combat these superbugs. Unfortunately, the current state of research into antimicrobial treatments is nowhere near where we need it to be to effectively combat the AMR threats we face today, not to mention those that we will inevitably confront in the future. We need to catch up now to ensure we have innovative antimicrobial products to meet current and future patient needs.

Currently, AMR receives significantly less funding for R&D than other diseases. Superbugs are on track to take 10 million lives a year by 2050 – more than cancer. Yet, in 2020, oncology companies raised almost $7 billion, while antibiotic research groups raised only $160 million.

That’s because the traditional economic model for developing and commercializing new drugs doesn’t work for the novel antimicrobials needed to fight superbugs. Companies can spend billions of dollars on developing and bringing to patients just one new drug. The return on this investment – under the typical drug development scheme – is based on unit sales of the medication once it achieves Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval.

Antimicrobials are fundamentally unique. These novel products face several challenges, including low volume of use – in part to ensure appropriate use – as well as insufficient recognition of their societal value to support modern medical care. Due to their unique challenges, these life-saving therapies need to be incentivized based on their value for public health instead of the volume used. It’s critical to public health that novel antimicrobials are used appropriately, as widespread use of novel antimicrobials would accelerate the rise of AMR. Unfortunately, sound stewardship principles conflict with antimicrobial developers remaining commercially viable. And the way that the federal government currently pays for antimicrobials fails to drive appropriate use or innovation.

As a result of this broken marketplace, many antimicrobial developers are often forced to abandon their projects or go bankrupt, leaving promising new superbug killers languishing in the lab.

We need to correct this market failure – and fortunately, we know a way that can help.

How to address antimicrobial market challenges

An essential solution is spelled out in the Pioneering Antimicrobial Subscriptions to End Up surging Resistance (PASTEUR) Act. This bipartisan bill would help align market incentives with critical innovation by establishing an alternative payment model for antimicrobials to treat the most threatening infections. Under this system, the government would enter into contracts with innovators to pay for consistent access to novel antimicrobials with payments that are decoupled from the volume of antimicrobials used. The subscription model under PASTEUR is an innovative way to pay for novel antimicrobials while supporting the pillars of appropriate use. We can thereby gain the leg up we need on superbugs.

The bill has broad support among a variety of stakeholders and is gaining critical momentum. In March, more than 230 organizations – spanning health care providers, hospitals, public health professionals, patient groups, the pharmaceutical and diagnostics industries, and more – sent a letter to Congress calling for the advancement of PASTEUR.

Superbugs will always persist – surviving pathogens will continue to evolve into antimicrobial-resistant strains. But if we leverage the policy solutions at our disposal to fix the broken ecosystem for antimicrobial development – including advancing PASTEUR – we can be prepared to fight them. The time to build our defenses is right now to ensure that clinicians have the tools they need to treat patients.