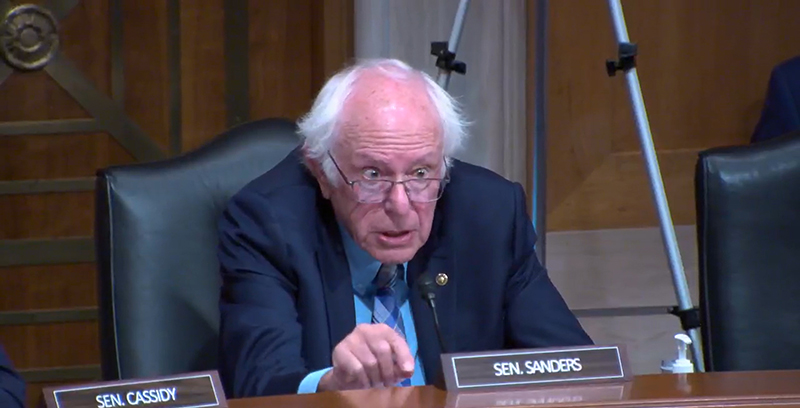

Yesterday, Sen. Bernie Sanders held a meeting about the new class of groundbreaking diabetes and weight-loss medicines. Next week, he will hold a hearing on the same topic.

Here are five realities about these innovative medicines showing why it is vital that we protect the innovation ecosystem, including intellectual property rights, to allow breakthroughs like these to get from the lab to the people whose lives can be transformed by such medicines.

Reality One: Anti-obesity medicines are a great value. The health benefits—along with the long-term cost-savings—from obesity medicines are well-recognized by economists. Even frequent industry skeptics, such as Affordable Care Act architect Ezekiel Emanuel and the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review have concluded that these medicines are cost-effective.

Reality Two: Costs are dropping, and that phenomenon is likely to accelerate. The net price of anti-obesity medicines has fallen dramatically—vials of GLP-1 obesity medicines are now available for less than $400 a month—and prices are expected to keep falling. Reuters has said that 16 new obesity medicines could be on the market within five years, creating enormous competition that will further drive down prices.

Reality Three: The anti-obesity medicines show the power of innovation. The first GLP-1 drug was introduced about 20 years ago. It required twice-daily injections and had middling efficacy. But because the life science ecosystem encourages continued innovation, these medicines have grown more impactful and more convenient, with utility in more diseases. Respecting and protecting intellectual property is a centerpiece of this successful innovation ecosystem.

Reality Four: Sanders has minimized the effect of the drugs on overall spending. In his initial report on the subject in May, Sanders wrote “whether weight-loss drugs achieve transformative savings should only be one consideration in their pricing. Pricing drugs based on their value cannot serve as a blank check.” Yet the link between value and price is not a “blank check,” but rather a guide to ensure that high-value care is incentivized.

Reality Five: Sanders has played fast and loose with the facts in this area. Sanders, in that May report, overestimated the number of Americans that might use obesity medicines and cherry-picked figures on the percentage of the health care economy that medicines represent. As we previously noted, Sanders has based part of his rationale for launching the investigation on a study attempting to determine a sustainable “cost-based price” for these medicines. That study has been criticized for its flawed methodology that disregards the full range of R&D costs in its estimate and for inaccurately suggesting that medicines should be priced based on their cost of production rather than the value they deliver for patients, the health system, and society.

Reality Six: Innovation is driven by predictable intellectual property protections. Sanders has promoted the idea that generic manufacturers could sell popular medicines for far less than the brand-name manufacturers. But the system is designed to encourage breakthroughs by rewarding innovation. Destroying that system by allowing generic competition based on political whims, not patent rights, would have a devastating effect in all therapeutic areas, not just obesity.

The power of obesity medicines is driving unprecedented demand, and managing that demand requires a thoughtful public conversation about how we prioritize health care dollars. We can’t let that conversation be overtaken by those whose sole goal is expanding government intervention in health care.