Going from “we have a problem” to “we have an idea” to “we have a solution” is an important journey for patient advocates and their family members in the rare disease community, said John Crowley, President & CEO of the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO), during his Sept. 26 keynote at the Global Genes RARE Advocacy Summit in Kansas City, Missouri.

The event’s slogan this year: “There’s no place like hope.” Ultimately, biotechnological innovation is facilitating that aforementioned journey, driven by the essential advocacy efforts of the rare disease patient community, added Crowley.

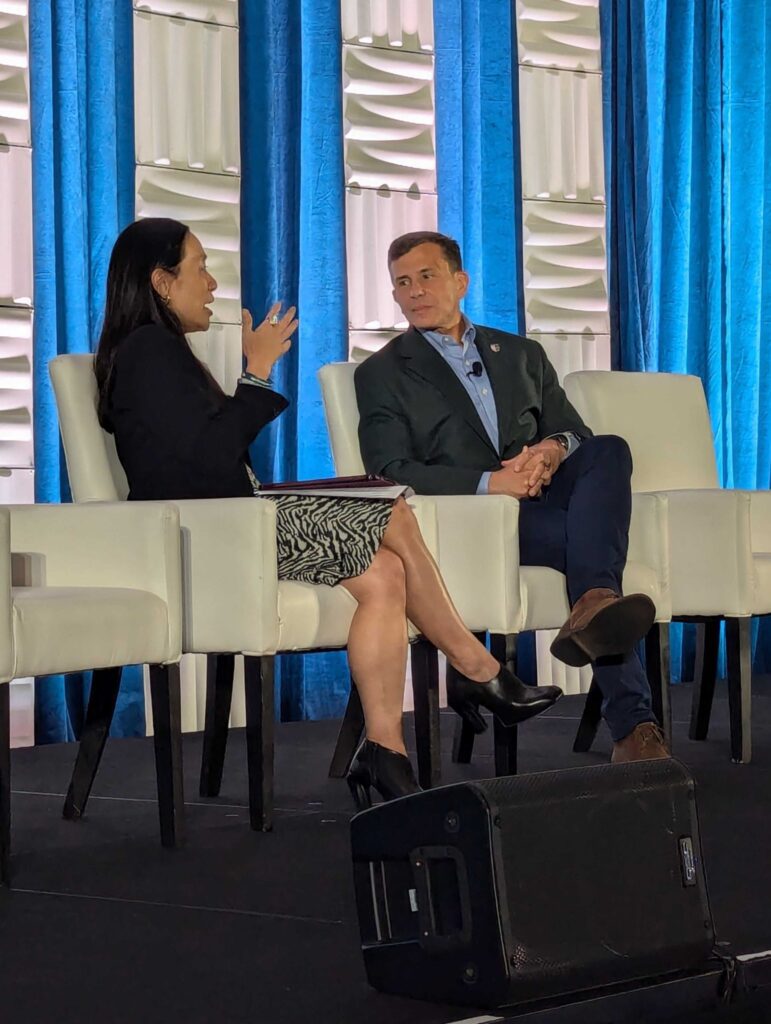

In a wide-ranging discussion with Global Genes CEO Charlene Son Rigby, who co-founded the STXBP1 Foundation after her daughter was diagnosed with STXBP1, a rare genetic disorder that can cause severe epilepsy, among other symptoms, Crowley shared his perspective as the father of rare disease patients—two of his three children live with Pompe Disease—and how this propelled him to become a biotechnology entrepreneur and industry advocate.

A 26-and-a-half-year journey

Crowley still vividly recalls receiving the news that two of his children had been diagnosed with Pompe Disease, 26 and a half years later. He shared how limited the resources were at the time and how much things have changed—not only in the advancement of therapies but also in the availability of information for patients and their families, as well as the sense of community in the rare disease space.

“Patients have options,” he said. “Families have hope…they have real outcomes.”

“But it’s still not enough,” he added.

He urged attendees to “no longer be satisfied with where we are [and] what’s in front of us.” Patients and their families should hold on to “that fierce sense of hope and that great sense of urgency.”

When a community said ‘enough’

“You look back in the late 1980s when HIV and AIDS was devastating, and a community said enough,” said Crowley. “They were incredibly vocal and incredibly active,” forcing policymakers and market regulators to take risks and prioritize innovation in treatments for people living with HIV and AIDS.

The first drug approved, AZT, was “a horribly toxic molecule, barely effective—but it was a start,” he said. But innovation since then has taken HIV from a death sentence to a long-term, chronic, manageable condition.

“That’s the type of passion and enthusiasm we need to bring to this,” he said.

‘These need to be entirely bipartisan issues’

Crowley also spoke of the need for strong bipartisan support on Capitol Hill for patient priorities that can facilitate the innovation of new treatments and new therapies.

“Whether it’s the pediatric review voucher reauthorization, the ORPHAN Cures Act, whatever it may be, these need to be entirely bipartisan issues,” he said. “There’s no left, there’s no right, there’s only back or forward.”

Crowley emphasized the importance of making the case directly to lawmakers—“going out and showcasing science” not only on Capitol Hill but also in the states.

“We also need to make sure we pass the ORPHAN Cures Act,” he emphasized, “so we don’t have that massive disincentive in the IRA [Inflation Reduction Act].”

“Nothing in the laws of nature says that we can’t cure every one of these diseases—only in the choices we make as people,” he said. “Let’s break down those barriers.”

The ‘unique role’ of patient advocates

Over the course of the conversation, Crowley commented on the role of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the approval process for new therapies and treatments for patients.

“At Amicus, I had a rule: you could not go to the FDA for any meeting unless you brought a patient or a parent with you,” he explained.

There is a “unique role that families, caregivers, patients can play when we talk about that virtuous circle—all the parts that have to come together—and how incredibly difficult it is to make newer and better medicines.” The patient and their family are at the center of that circle, because innovation must “be an entirely patient-led revolution.”