HIV is not the death sentence that it was decades ago. Yet, there is still much work to be done in the HIV advocacy and public health realm, and the disease is still widespread. During December’s HIV/AIDS Awareness Month, Bio.News spoke with the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute about the state of HIV drug innovation and what still needs to be done to support patients and increase their access to medicine.

“Over a million people in the United States have HIV,” says Carl Schmid, Executive Director at the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute. According to HIV.gov, of those approximately 1.2 million patients, around 13% “don’t know it and need testing.”

“People don’t think about HIV as much as they used to,” continues Schmid. “They think it’s a solved issue, but no—we still have over 30,000 new infections every year.” Testing and timely access to treatments are essential.

“To remain healthy, patients must stay on their medication, which is a lifelong commitment,” Schmid says. “While we have great drugs, getting them to the people who need them remains a challenge. Numerous barriers exist—socioeconomic barriers, insurance barriers, and issues with health coverage. Many people can’t access the drugs they need due to cost, formulary restrictions, or lack of coverage.”

HIV patients have options

“We have exciting products on the horizon,” says Schmid. “In the past, there were no treatments or drugs for HIV. In the 90s, people were just dying.”

In the early years of the AIDS crisis, patients had an average life expectancy of one year following an AIDS diagnosis. The first drug to treat AIDS—the first antiretroviral—came out in 1987, part of a class of drugs referred to as nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, or NRTIs.

This innovation was followed by combination therapy in 1995 after the limitations of single-drug treatment regimens became apparent to researchers. A year later came triple-drug therapy, which combined drugs from at least two different classes (e.g., a protease inhibitor and two NRTIs), resulting in HIV suppression within the immune system.

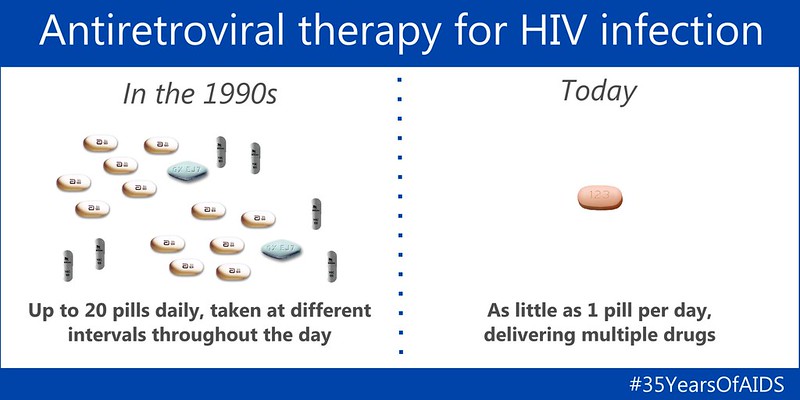

And while these early therapies extended life expectancy among patients, there were side effects. It took decades for HIV maintenance medication to go from a side-effect-heavy, complicated, multi-pill-a-day dosage process to what we have now.

“There are well-known stories of early patients experiencing wasting syndrome,” explains Schmid, “but now most patients experience a normal weight and see better outcomes overall. Now, we have long-acting drugs. For treatment, we’re at the point where it’s once every two months, and the same progress is happening for prevention.”

HIV maintenance and suppression therapies, as well as preventative treatments for those vulnerable to HIV coupled with education, are key elements to eradicating the HIV epidemic. “For prevention, we’re seeing advancements that might lead to a once-every-six-month injection [being available] as early as next year. Long-acting treatments are making it much easier for people to adhere to their medication and stay on track.”

There are currently two preventative, once-a-day dosage drug options to prevent the contraction of HIV, but there is still work to be done when it comes to getting these drugs into the hands of patients.

Why access to preventive measures needs to improve

“We have excellent new prevention drugs, but again, testing, education programs, and insurance coverage through Medicaid, Medicare, and other insurers are crucial,” explains Schmid. “Unfortunately, we still face significant racial and ethnic disparities in access and care.”

There are a number of issues when it comes to prevention, treatment, and education, but the largest two areas are social stigma/bias and institutional healthcare policy.

“Talking about HIV means talking about sex, and many doctors are uncomfortable discussing sex,” says Schmid. “In the South, where many cases are concentrated, you also have to address topics like homosexuality and different sexual practices. Unfortunately, doctors don’t always talk about these issues.”

Disparities among LGBTQ+ patients are not the only issues when it comes to stigma; racial disparities pose significant barriers, as well.

“Racial disparities in HIV are huge, whether you’re gay, Black, Latino, or living in the South,” says Schmid. “There’s still a lot of stigma associated with it, so providers don’t always prescribe or talk about these issues with certain populations.

According to HIV.gov, “Black/African American people accounted for 37% (11,900) [of the HIV+ population], even though they made up 12% of the population.” They are also the fastest-growing HIV population in the U.S., with Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino making up more than half (70%) of estimated new infections in 2022, according to the CDC.

“To effectively address HIV, we need a welcoming and supportive healthcare system—one that fosters trust and is open to discussing HIV, prescribing treatment, and providing prevention options,” says Schmid.

Why coverage needs to improve

“We’re finding that some insurers aren’t covering the HIV drugs people need,” explains Schmid. “Recently, we filed discrimination complaints against certain insurers—first, for not covering the drugs or following treatment guidelines, and second, for placing all HIV drugs on the highest tier. That’s pure discrimination and a violation of the Affordable Care Act.”

Drugs on the higher tiers of health insurance plans are usually more expensive for patients than those in lower tiers because of greater cost-sharing requirements.

As recently as November 2024, the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute filed five discrimination complaints (in five states) against two insurers. Not only did the insurers place even generic HIV drugs on the highest cost tier, but they also refused to cover drugs recommended by national HIV treatment guidelines, including single-tablet regimens. The Institute filed similar complaints in Texas and North Carolina.

“Since the copay for Tier 5 can be $500, $850, and even 50% coinsurance, depending on the plan, people living with HIV can face out-of-pocket costs higher than the list price of their drug,” writes the Institute.

This month, the Institute marked another win in Maine with a discrimination suit against an insurer for removing HIV drugs from their formulary. As a result, the insurer added the most widely used HIV drug on the market today. The Institute is now waiting for the ruling of similar suits in Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Minnesota, Iowa, and Texas.

Insurers are also manipulating copay accumulator programs.

“HIV drugs have always been expensive, and drug companies have offered copay assistance programs to help people afford them,” says Schmid. “However, insurers are now saying they will accept the co-pay assistance but not apply it toward a person’s out-of-pocket costs or deductible. We’ve been fighting this policy for years, even going to court—and we won.”

However, there is a surprising issue related to copay accumulators: “Unfortunately, the federal government, believe it or not, is not complying with the federal court decision on patient out-of-pocket costs. They said they would issue a new regulation over a year ago, but it still hasn’t happened.”

The Institute is now forced to urge the Biden-Harris Administration to comply with the court’s order. “We’re encouraging them to simply comply with the order,” says Schmid. “If they don’t, we’ll have to start all over again with the new administration, and that will take a long time. In the meantime, patients are being harmed—they’re being forced to pay thousands of dollars they didn’t expect while insurers and PBMs profit from it. They collect money first from the drug manufacturer and then from the patient.” Schmid says this is a surprising move by an administration that has publicly voiced an interest in lowering patient out-of-pocket costs.

To learn more about the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute, visit hivhep.org.