As drug makers work to develop safe, effective gene therapies, their progress can be slowed when they challenge the limits of established regulatory guidance on expectations for study designs. The most innovative therapies and approaches often do not fit into established practices for drug development and become case-by-case discussions with regulators to align on the best approach. A group of biotech researchers is seeking to help.

Gene therapies are medical products that seek to treat or prevent diseases with a genetic component by modifying the relevant gene. This could mean inactivating or replacing a gene that isn’t functioning properly, or even introducing a new gene to help cells fight disease. Examples of diseases where gene therapies have been developed or are being pursued include sickle cell disease, hemophilia, cystic fibrosis, heart disease, HIV, and some cancers.

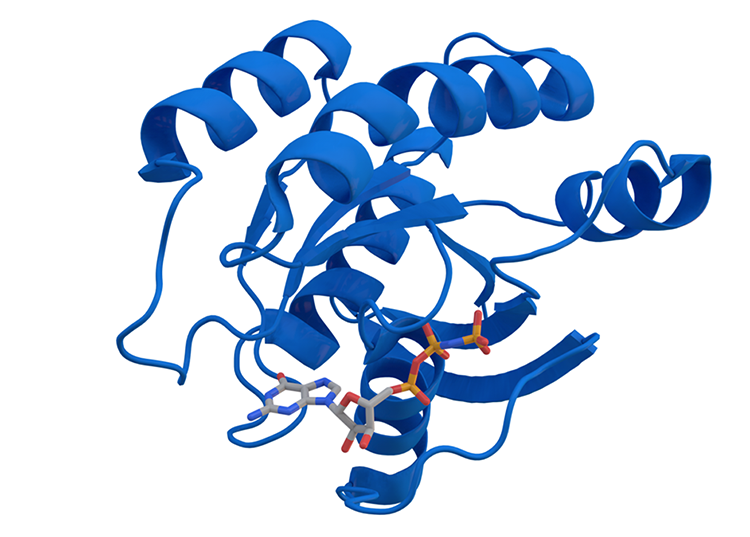

These therapies work by using a vector, or carrier, to deliver the new/modified gene into cells where it becomes integrated in the cells’ DNA, directing them to make “normal” protein. One commonly used vector is adeno-associated virus (AAV). AAVs are viruses that don’t cause disease in humans and are effective at reaching specific types of cells

While gene therapies sometimes work with a single application—eliciting long-term or even permanent expression of the desired gene—there are situations where it becomes necessary to deliver a therapy a second time, or to give repeated doses. This could be because the first dose was insufficient to produce the desired outcome, the disease is progressing, or for other reasons.

Challenges to redosing may arise because the body’s natural defenses can end up preventing these specially formulated viruses from delivering gene therapies.

Members of BIO’s Cell and Gene Therapy Nonclinical Task Force collaborated on a research paper that discusses ways to respond to the challenge of immune responses hindering redosing of gene therapies. Specifically, the manuscript outlines nonclinical study design considerations based upon their collective experiences, which could help facilitate productive conversations with regulators to address this emerging opportunity for redosing gene therapies.

“New immune modifying techniques and emerging delivery platforms are being developed to overcome these limitations,” the BIO group’s paper says. “Despite these advances, there is currently no regulatory guidance on how to design nonclinical studies to enable clinical redosing.”

Suggestions for solutions

The paper seeks to articulate the current state-of-the-art regulatory science to address these issues. First, it details some solutions being investigated to get around immunity to AAVs, including eliminating certain types of antibodies, suppressing the immune system with steroids, and altering the capsid—the protein shell of the virus. Then it recommends guidance for nonclinical studies on how to evaluate these potential therapeutic solutions.

Products designed to overcome immunity to AAVs might have to be developed and tested separately from the AAVs themselves, the paper says.

“This could involve separate nonclinical safety studies and traditional development approaches for each product. Once supportive safety and efficacy data are obtained, clinical co-development with the gene therapy in the intended patient population can be explored,” the authors explain.

The authors make several recommendations for ensuring that nonclinical redosing studies achieve the desired goal of demonstrating that subsequent doses have similar safety and efficacy profiles as the original doses, so that they are more likely to be acceptable to regulatory authorities, like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA):

- A study period of no longer than six months should be sufficient.

- Redosing should take place at a time point where maximal expression has occurred and sufficient time for an immune response has elapsed, but the dosing should not have to directly model the intended clinical use.

- Nonclinical studies should include animals that have neutralizing antibodies, which means exposure to the capsid is necessary—ideally by dosing the animals with the AAV containing the therapeutic.

- The bioanalytical strategy should suitably measure the pharmacodynamic response, biodistribution, and immunogenicity of the AAV gene therapy. Where appropriate, it should also consider the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the immune modulator.

- Nonclinical endpoints of the safety studies should be consistent with standard toxicology studies for AAV gene therapy.

The authors say they hope their recommendations will be used to establish clear regulatory guidance for designing nonclinical studies that enable clinical redosing of gene therapy products.

“Collaboration and consultation with health authorities through formal processes are encouraged to develop innovative therapies that minimize patient risks and address the unmet needs that even the most effective single-dose gene therapies cannot fully meet,” they write.

BIO’s BioSafe Committee

Often times, gene therapies are developed by small biotechs that focus on a single disease or therapeutic approach. These companies may have never worked with global regulatory authorities to navigate the drug development process. Uncertainty is one of the biggest challenges for drug development, specifically knowing what data are expected by regulatory authorities and how to best design studies to produce them. Regulatory authorities put out formal guidance to clarify this process. Additionally, there are prescribed meeting types companies can take advantage of at specific times during the drug development process to align with regulators on expectations.

However, the more innovative and novel the therapy, the more uncertain the expectations can be for the drug development process. This is where organizations like BIO can collectively identify areas of uncertainty and work collaboratively to propose solutions that are data-driven and experiential in nature.

Efforts like this manuscript from members of BIO’s Cell and Gene Therapy Nonclinical Task Force seek to educate and share the collective experience in drug development across the industry and improve the quality of regulatory submissions with appropriate, efficient, and compelling datasets.

The task force is part of BioSafe, BIO’s nonclinical safety committee. BioSafe includes more than 300 BIO members and seeks science-based responses to scientific and regulatory challenges and developments in nonclinical safety evaluation of biopharmaceutical products.

BioSafe’s work is part of a natural process. The science and technology are advancing rapidly and often outpace updates to regulatory guidance. By helping to map out best practices based upon their experiences, the biotech community can educate the regulatory community and provide a starting point for case-by-case discussions with regulators.

Each year, BioSafe hosts a face-to-face General Membership Meeting (GMM) that features presentations and networking sessions from industry and government institutions. They identify pressing issues that need clarification and then the various task forces produce outputs like the manuscript.

“We’ll often identify topics or issues that are shared broadly across large and small companies and figure out how they want to address those. Writing a paper is one thing that companies, through BIO task forces, can do to get their ideas out there,” notes Libby Barksdale, Sr. Director of Science and Regulatory Affairs at BIO.

“The hope is to dovetail with regulatory authorities on these industry challenges,” Barksdale explains. “One of the roadblocks for small companies, especially, is the need for greater insight and clarity on expectations. BIO can help bridge that gap by facilitating discussion amongst member companies and encouraging the sharing of industry best practices, while continuing to engage in productive regulatory dialog to promote clarity and expectations.”