The 340B program, in recent decades, has shown how the best laid plans can go sideways when not kept transparent and properly in check. Initially intended to help safety net hospitals further serve vulnerable communities, the program has now ballooned into a massive profit generator for hospitals that aren’t necessarily passing the savings on to patients.

But what are we to do about this issue?

This was a big question at the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) Patient Advocacy Changemaker’s Event (PACE) in Washington, D.C., where advocates talked about increasing the transparency of 340B and getting it back to its original intent.

What is 340B?

“340B is a federal program that requires manufacturers to provide discounts on outpatient drugs for certain entities,” explained Anna Hyde, Vice President of Advocacy and Access at the Arthritis Foundation. “And when you think of a discount, think of 50–60% off what a non-340B hospital would pay. The intention was really for the savings to help safety net hospitals bolster access and help further serve vulnerable patients.”

“But today, 340B is now the second largest federal prescription drug program behind Medicare Part D—think of about over $50 billion when you think of this program,” she continued.

As Hyde pointed out, government and others have started calling into question the use of 340B funds. This awareness grows as it is coupled with growing medical debt and consolidation.

“Imagine 340B as the head of an octopus, and it has its tentacles in several things,” including pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), explained Hyde. “If you care about PBM reform, you should care about 340B. If you care about coverage, you should care about 340B. If you care about consolidation? Guess what? You should care about 340B.”

What do we do next?

But, really—what is 340B?

The first place to start is the fact that the 340B program fundamentally lacks transparency.

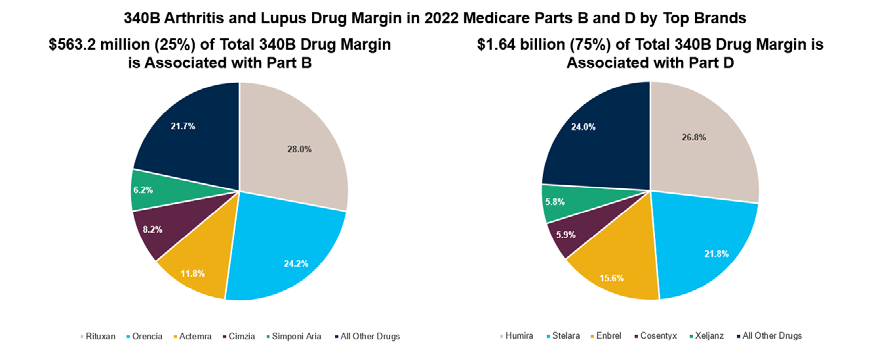

When Hyde and Patrick Wildman, Senior Vice President, Advocacy & Government Relations at the Lupus Foundation of America, looked at revenue associated with the 340B program for their two respective disease areas, lupus and arthritis (examining three state Medicaid programs: California, Oklahoma, and Alabama), they were shocked.

“When looking at lupus and arthritis drugs together, and looking just at Medicare Part B, D, and three Medicaid programs—pretty small in the grand scheme of things, since that doesn’t include commercial or the other 40 or so Medicaid programs—the 340B revenue, taking all those variables into account, is over $2 billion a year, which is wild to me,” Hyde said.

“If you extrapolate that to the entirety of all of the markets combined,”Hyde continued, “I can’t imagine what that number adds up to.”

Where is that revenue going? Is it going to charity care as intended? Is it saving vulnerable populations money as intended? As Hyde explained, not necessarily. In fact, researchers had a hard time figuring out where the money was going at all.

This lack of transparency becomes an even bigger issue when considering that 340B is also a driver of hospital consolidation, which can end up costing patients more.

“As hospitals are purchasing independent clinics, the cost of care at those clinics is cheaper and the cost of care at the hospital is higher,” explained Brian Connell, Vice President of Federal Affairs at the Blood Cancer United (formerly the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society). ”For example, when a hospital buys a physician-owned infusion center where folks are getting chemo, once the name plate on the door changes to that of the hospital system, suddenly that exact same care costs more for the patient.”

“And the data actually shows that 340B is really a driver of that consolidation,” he stressed.

‘You can be a 340B patient and have no idea’

Kimberly Beer, Senior Vice President, Policy and External Affairs at the National Health Council, likens patient access to information to a game of policy whack-a-mole.

“Once we solve a problem here, another one pops up over there, and it’s really difficult for the patient to really understand how their life may be improving or becoming more complicated,” said Beer. “It feels as if they’re just additional layers for them to have an efficient experience within the healthcare system.”

“I think what’s frustrating for patients about this program is that it’s a complete black box,” said Connell. “You can be a 340B patient and have no idea that you’re a 340B patient.”

Transparency as a first step

“I think the low-hanging fruit is around transparency,” said Hyde. “That’s the white hat component that I feel like it’s hard to argue against.”

Once advocates and legislators understand where the dollars are going, they can understand how to protect patients’ pocketbooks.

“Our work has been more trying to assess the programs and see what the impacts are,” said Wildman. “But then we come up with principles, and really try to hammer home the core principles that we want to see in a healthcare system, whether it’s transparency, out-of-pocket cost, charity care, or aggressive medical debt collection practices. That’s where we focus, and I think some of the next steps are going to be getting into the details of exactly how we address this massive 340B machine.”

Connell agreed: “Transparency seems to be where the oxygen is right now, at least on the federal level.”