The COVID pandemic brought the world to a standstill in 2020. Only within the last year or so have things started to get back to normal—or, at least, a new normal. Yet, less than a decade after the onset of the novel virus, we’re already starting to lose the lessons learned. Healthcare professionals, researchers, and biotech companies continue to remind the world that it is not a matter of if there will be another pandemic, but when.

Ginkgo Bioworks is working to understand the mechanics of the COVID pandemic, as well as what could cause the next pandemic and when. Recently published research by the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) member company aims to project and understand the probability of the next pandemic and what we can do to avoid it.

The next pandemic?

A zoonotic spillover event is a fancy way of describing how a disease that previously existed only in one species mutates and jumps to infect another species. This is likely how the SARS-CoV-2 virus got started, and it has been long theorized that exposure to rare animals in a Chinese wet market is to blame. This phenomenon has been observed in a number of other viral pandemics, including the AIDS virus and several flu pandemics.

As such, Ginkgo Bioworks is focusing its research on spillover events to calculate the probability of another global pandemic occurring. Their findings were humbling.

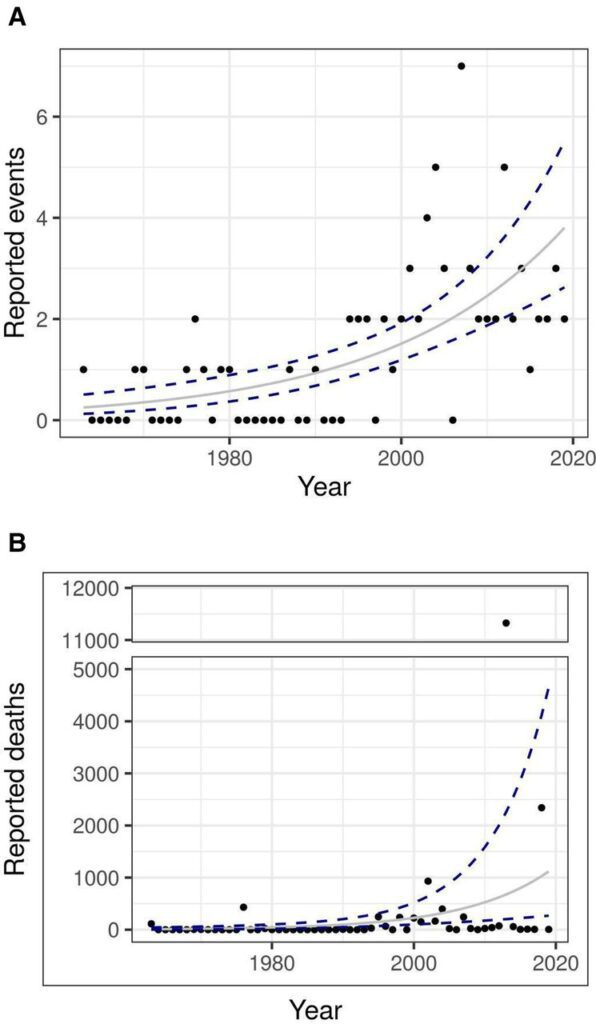

“We utilized our extensive epidemiological database to analyze a specific subset of high-consequence zoonotic spillover events for trends in the annual frequency and severity of outbreaks,” explains the paper’s abstract. “Our analysis, which excludes the ongoing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, shows that the number of spillover events and reported deaths have been increasing” by 4.98% and 8.7% respectively, each year.

But what exactly does that mean?

“That means there’s a 50-50 chance we’ll have another one before the year 2049,” explained USA Today.

To understand the risk, it’s important to explore how novel diseases arise and why the risk is increasing.

The nature of zoonotic spillover events

First, we need to understand the nature of spillover events and how they are linked to climate change and the destruction of natural environments.

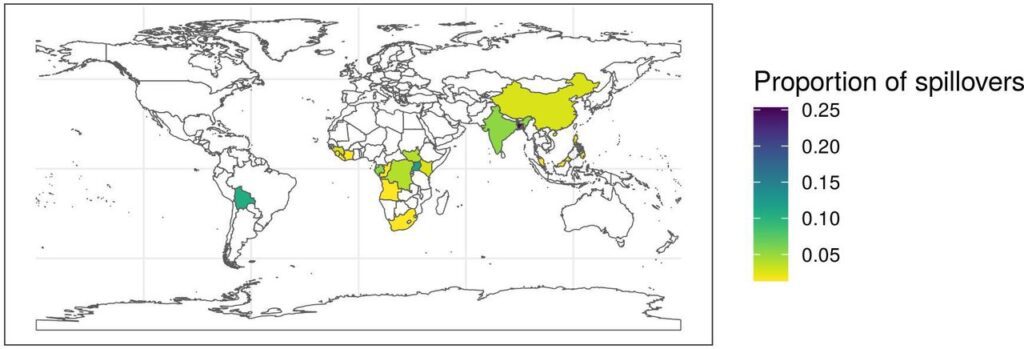

Historically, many diseases were geographically and ecologically bound in areas that humans could easily access, or where more fixed (and therefore more inoculated) groups and tribes of people lived. Two major things have changed with the rise of modernity and globalism in the last few centuries: the temperature of the earth is increasing, and deforestation is increasing. Put simply, novel diseases with the potential to spill over are not only being exposed more to humans but they are also being provided with better conditions for mutation. And, not surprisingly, the areas with the highest number of spillover events typically have warmer climates, increased instances of deforestation and mineral extraction, and often are tropical.

Since these two environmental trends are not letting up, the increasing likelihood of spillover consistently increases.

“We find the number of outbreaks and deaths caused collectively by this subset of pathogens (SARS Coronavirus 1, Filoviruses, Machupo virus, and Nipah virus) have been increasing at an exponential rate from 1963 to 2019,” the study explained. “If the trend observed in this study continues, we would expect these pathogens to cause four times the number of spillover events and 12 times the number of deaths in 2050, compared with 2020.”

“This study suggests the series of recent impactful spillover-driven epidemics are not random anomalies, but follow a multi-decade trend in which epidemics have become both larger and more frequent,” the study continued. “These findings provide additional evidence that concerted global efforts to improve our capacity to prevent and contain outbreaks are urgently needed to address this large and growing risk to global health.”

How do we prevent the next pandemic?

Ultimately, countries worldwide have a good idea of what needs to happen to combat that next pandemic before it starts. The problem, it would seem, is consensus.

As Bio.News has reported, there are five areas to start preparing:

- Sustaining a thriving innovation ecosystem that can be counted on to deliver rapid research and development of new pandemic countermeasures.

- Establishing a new social contract to reserve a portion of the immediate production of pandemic vaccines and treatments for priority populations in low-income nations and taking steps to make them accessible and affordable.

- Promoting worldwide sustainable manufacturing that can expand for high-volume supply in the event of pandemics.

- Supporting an environment that levels up global health security and an open-border policy without any restrictions that will enable the free movement of vaccines, treatments, and their raw materials and supplies, as well as the movement of people needed to support their manufacturing by sharing technical know-how.

- Aiding ongoing initiatives to improve national preparedness to foresee and respond to pandemics by investing in vital health system components, such as life-course immunization programs.

“The best outcome during an emergency comes from partnerships during the interpandemic period, when there is time to make thoughtful investments,” BIO Senior Vice President of Infectious Diseases & Emerging Science Policy, Phyllis Arthur, told the UN back in September 2023.

“Governments and stakeholders must work together to expand clinical trial networks, strengthen national regulatory capacity and harmonization, build stronger supply chains, and incentivize manufacturing across regions. Sustained public and private funding is essential for robust R&D. Government and industry should invest in new platform technologies and mechanisms for the development of vaccines and antivirals against the most important pandemic pathogens,” she said.

“In addition, governments, in partnership with manufacturers, should invest in geographically diverse regional manufacturing expansion during the period between pandemics. This will aid in the development of new technologies that could be rapidly deployed around the world,” continued Arthur.

The risk of another pandemic is not a risk that is waning. And each year without a global pandemic preparedness plan in place, invested in, and improved upon is another year we face preventable and unnecessary risk.