The Black Coalition Against COVID (BCAC) was born on Easter Sunday 2020. Dr. Reed Tuckson, the organization’s co-founder recalls, “We looked at the data and saw what a challenge this was going to be for the Black community.

-

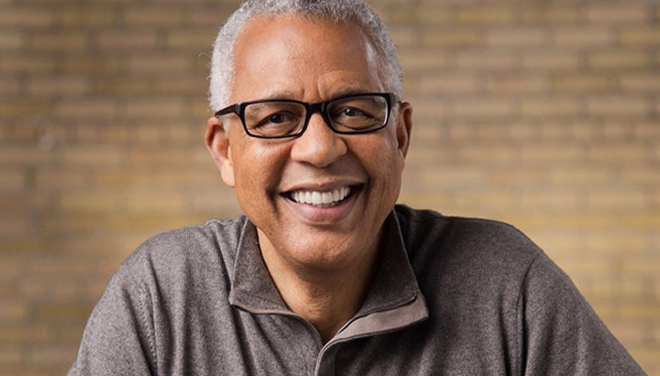

Dr. Reed Tuckson, M.D., President of the Black Coalition Against COVID - “So, drawing on my experience as the Commissioner of Public Health for Washington D.C. during the height of the AIDS epidemic in the 80s, I knew that we had to build a grassroots effort that could marry with the government to work collaboratively from the top down and bottom up.”

Black doctors in particular were facing steeper challenges as they dealt with the COVID pandemic in their communities. As Reggie Ware, the CEO of the Black Doctors Organization (BDO), recalled to the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO), “When COVID first came out, there was an overwhelming consensus within the Black community that they were not going to be as affected by COVID as other populations. And so, we had to start educating people that this thing is going to go worldwide.”

Tuckson has been a consistent collaborator with organizations like BDO, and together withBCAC and others, they were able to turn the tide when it came to the COVID burden in the Black community, saving untold numbers of lives via outreach, education, and empowerment.

“We began reaching out to community-based influencers in the D.C. area who I knew still had an active role and a trusted voice. We worked with leaders in the faith community, the medical community, academics, advocates for returning incarcerated citizens, community-based organizations, visual artists, poets, musicians, and some small business owners. We made sure we worked across the board. Eventually, the grassroots effort grew and segwayed into our national effort.”

A history of care

Tuckson, like many of his colleagues, has devoted his life to public health in the Black community. His history was key to informing his work during COVID.

“I was fortunate to be the health commissioner during a time of great challenge,” he recalls. “It was a very difficult job and we were not only fighting against the AIDS epidemic, we had to contend with addiction epidemics like crack cocaine, major heroin overdoses, angel dust, as well as more traditional challenges like infant mortality, cancer, heart disease, and so forth. The thing that you learn from that work is that health is the place where all the social forces converge to express themselves with the greatest clarity. Health is where everything comes together.”

The Black community, in particular, has a distinctly higher number of negative social determinants than their white counterparts. And increasingly, doctors understand more and more what effect that has on public health.

“Some of the worst social determinants of health in the Black community are hopelessness and despair,” explains Tuckson. “If you’re a young man, and you don’t believe you’re going to live past 20 because homicide is the leading cause of death for you, why worry about potentially having cancer when you’re 45, or having heart disease when you’re 50. But there are also additional issues of housing insufficiency and the inadequacy of the food supply. Many Black neighborhoods have access to very few grocery stores with fresh fruits and vegetables. So you start seeing all of those elements play out together.”

“Now that being said,” Tuckson reminds, “one of the great lessons that we have learned in this pandemic is that every community, no matter what its deficits, has its fair stripes.” And indeed, Black doctors soon utilized the many strengths in the Black community to protect it as best they could despite the challenges.

Changing the tide

“The shift in perception of COVID in the Black community was right off the bat,” Tuckson recalls. “The initial opposition to any outside influence was so heavy, particularly because of the issues of distrust in medicine. Memories of Tuskegee reared their ugly head once again. But over time, we did see that shift.”

By polling the community on sites like BDO, Black doctors were able to connect directly with their patients to see what worked and what didn’t through polling, webinars, and the like. Coupled with the outreach done by the myriad community leaders that organizations like BCAC partnered with, the way the Black community talked about COVID changed. This ultimately saved many lives that would have otherwise fallen by the wayside as a result of a mainstream medical system that is still filling in large blind spots when it comes to the Black community.

“It started to shift in a way that was amazing for all of us to observe,” says Tuckson. “For the first time, we closed the disparity gap in health care between Black health and white health—and we closed it in a year. White life expectancy now is hit harder than Black life expectancy when it comes to COVID because their folks are not wearing their masks, and they are not getting vaccinated,” Tuckson points out. “And Black communities are now better about taking and maintaining COVID precautions. We shifted from running a race with an anvil on our backs, while our opponent received a brand-new jogging suit and tennis shoes, to being in the lead.”

Lead with love

“The number one thing we as Black doctors have to do is to demonstrate love for our patients,” says Tuckson. “We’ve got to get the trust back.”

Undoubtedly, the banding together of Black doctors in America to combat the COVID pandemic was a profound act of love that saved untold numbers of lives. It is a remarkable example of how collaboration, conversation, and community are major players when it comes to promoting public health. Additionally, doctors like Reed Tuckson and organizations like BCAC and BDO understand that the work is not over.

“Our number-one goal now is to get ready for the future,” says Tuckson. “And part of that is being able to make sure that we’re learning how to continually communicate with people in an effective way in order to overcome the dispersion of invasive, pernicious misinformation. Secondly, I think that we really will have to deal with the issues of long COVID. There are many people today still dealing with this issue and it is a real problem.”

Tuckson concludes, “Thirdly, I think we’re going to have to manage the reality of this as an endemic disease, meaning that we will have to gear up for the next round of either mutations and vaccines, and make sure that we now use the lessons we’ve learned about how to conduct effective immunization campaigns. The work is far from over.”