The use of AI tools in the workplace is on the rise. This trend is equally true in the arena of patent practice. However, given the unique and complex needs of the legal field, it is of paramount importance to know how to use AI tools, the ethics of using these tools properly, and what tools are best for patent-specific needs.

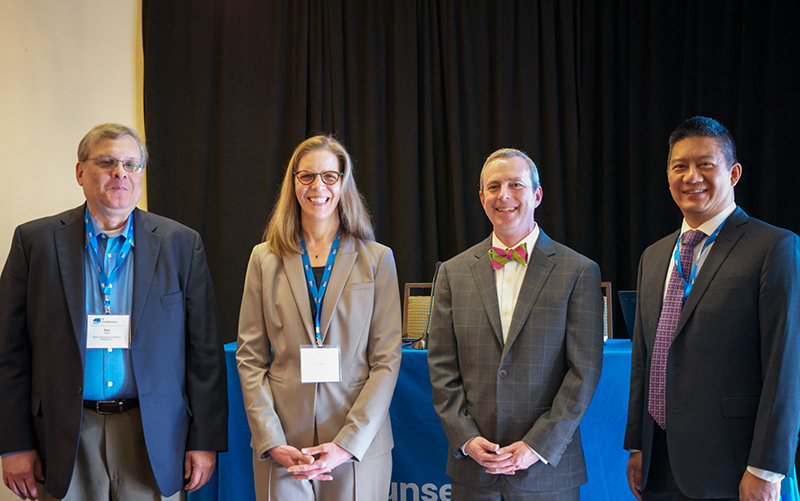

Such was the conversation at the Biotechnology Innovation Organization’s Intellectual Property Counsels Committee Conference Nov. 19 panel, “Using AI In Patent Practice: Practical and Ethical Issues.”

So, what are some of the ins and outs that patent attorneys need to know about using AI in their practice?

Know what AI is available

To kick off the conversation, Ann McCrackin, Adjunct Professor at UNH Franklin Pierce School of Law and Founder of AI-Enabled Attorney LLC, discussed the myriad AI tools that patent professionals could use in their practice—both generalized and specific.

To start understanding what tools are appropriate, she said, patent attorneys need to understand the difference between traditional AI (which is reactive and uses specific rules to analyze data and produce an output) and generative AI (which is proactive and uses data patterns to create and generate an output).

“There’s a lot of stuff that’s using what I would call just traditional AI,” McCrackin explained, “like natural language processing and machine learning. You might use that for prompts like take a method claim and reformat it as a device claim, for example. Or even for generating a summary section.” Yet, she noted, “You probably don’t want your summary section written by generative AI because of the need to precisely repeat the claim language. But you might use generative AI for a background section, or maybe to add some general description for something in your detailed description.”

McCrackin separated AI tools into three categories: specialized AI tools, including patent-specific AI tools; generalized AI tools, like ChatGPT, Gemini, Copilot and Claude; and patent proofreading tools.

The general AI tools are great for everyday needs: drafting emails, getting summaries from calls, etc. She added that general AI tools can also perform many of the same patent drafting and analysis tasks offered by patent specific AI tools. She cautioned, though, that any work involving confidential information must be done in a secure enterprise tier of the tool and never in a free version. And similarly, patent proofreading tools can be incredibly helpful when checking an application or patent for critical errors under 35 USC 112.

But when it comes to patent-specific AI tools, McCrackin noted, you have to know what you are getting into and be sure to demo as many tools as possible, because these tools are very expensive and vendors aren’t always going to tell you how the tools are working behind the scenes or where the constraints are.

“If you’re working in one of these tools, you’re providing a prompt or some instruction that is then going through the third-party vendor’s interface before it gets passed to ChatGPT behind the scenes.” McCrackin said. “They may be modifying your prompt. They may be adding something to it.”

But even as firms find AI tools that work for them, they still need to understand the ethics of their use.

Understand the ethics of AI

As Joshua Rich, Partner at Lippes Mathias LLP, explained, there are many ethical considerations that attorneys and their colleagues might not necessarily realize constrain them when using AI tools to draft and work on documents.

“We’re all familiar with the fact that generative AI can hallucinate,” Rich said. “It’s most apparent in our field in litigation, because there’s opposing counsel to call you out on it.”

One instance of a generative AI hallucination that made waves in the legal arena was the 2023 case of Mata v. Avianca, Inc., in which attorneys were sanctioned for using fake case law citations generated by ChatGPT, with the Court ultimately dismissing the personal injury case.

Similarly, two Federal judges have issued (and quickly retracted) opinions that included hallucinated case citations and quotations from generative AI tools. In one of them, it turns out that an intern was responsible for the AI-generated content, despite being explicitly told not to use AI tools by both the judge and his law school. The judges, for their part, did not catch the mistake before the briefing was filed. And if it is happening in Federal judges’ chambers, it is a risk that law firms and companies will have to look out for and figure out how to prevent. And that is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to AI ethics.

Unlike with inequitable conduct, “There is no empty mind, pure heart defense to ethics,” Rich noted.

One example Rich discussed is the fact that AI platforms like ChatGPT are public and when users work with these platforms, AI is learning from them and storing data.

“You’ve got a great patent,” he explained. “It’s perfectly strong, and a very narrow rifle shot to the infringing product. But as you’re getting into discovery in the litigation, you get the opposing counsel asking, So, how did you develop these data tables? And your inventor’s answer is, Oh, I typed it into ChatGPT. Is that a public disclosure? We don’t know yet, and that is going to be something that will be litigated and will be resolved down the road, but it is a problem that can be avoided.”

Another example Rich provided was a case in which a client comes to a lawyer and says, Hey, we just wrote this brief in ChatGPT, it’s all good, and we need you to put your name on it and file it. That is undoubtedly a situation where lawyers will face and will have to have the strength to respond, Not me.

Learn how to use AI effectively

Provided that a law firm now has an AI platform that they love, they need to start being able to use it. That is where Aaron Gin, PhD, Partner at McDonnell Boehnen Hulbert & Berghoff LLP, came in to explain some best practices for lawyers working with generative AI tools.

He explained that the best way to utilize such tools is to understand the elements of a good prompt by defining:

- the persona/role and objective;

- clear instructions, output format, and constraints/guardrails;

- contextual information; and

- success criteria and examples of desired output.

“You can’t just provide a bare prompt without source documents that the output can cleave to,” Gin explained. “Set clear guardrails. Show it what “good” looks like with a template. It’s also so important to iterate with these models. When you give it the initial prompt, you need to review the output and be critical about what the model is providing, and adjust the prompt as needed.”

Ultimately, AI usage in the patent, and overall legal, space is inevitable. That is why it is required of lawyers to stay up to date with the technology as it evolves. It is not just a work requirement, it is an ethical requirement too.