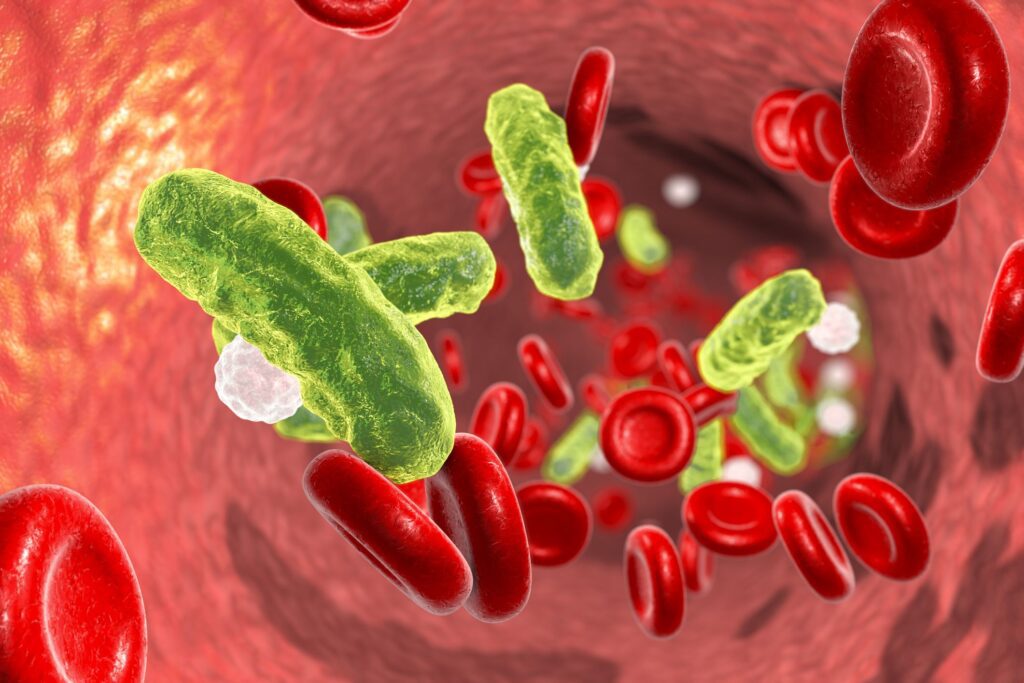

As part of BIO’s March Patient Advocacy Coffee Chat, Thomas Heymann, President & CEO of Sepsis Alliance, spoke about sepsis—a life-threatening condition caused by the body’s immune system overreacting to an infection—and its link to rare diseases and antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

What is antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and how is it connected to sepsis?

Antimicrobial resistance—or AMR—occurs when the bacteria, viruses, or fungi that make people sick adapt to the antimicrobial medicines designed to treat them and become resistant to those medications. These drug-resistant pathogens, also known as superbugs, are currently putting millions of people at risk of developing life-threatening, untreatable infections. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), someone in the U.S. dies from an AMR infection every 15 minutes, amounting to nearly 100 people every single day.

AMR challenges the treatment of sepsis. While broad-spectrum antimicrobials are often the first line of defense in treating patients with sepsis, it is crucial to utilize antibiotics appropriately through principles of antimicrobial stewardship. As more pathogens become resistant to the medicines used to treat them, more people are at risk for developing sepsis. As AMR worsens, sepsis cases will, in turn, become increasingly difficult to treat, leading to more sepsis patients suffering harmful consequences such as amputations and death. To manage this complex clinical relationship, address the global threat of AMR, and improve future outcomes, cross-sector collaborations and ongoing innovation and education are essential.

In that respect, sepsis shares a lot of similarities with rare diseases.

What do sepsis and rare diseases have in common?

Heymann highlighted how the sepsis and rare disease communities are surprisingly closely aligned, noting that, similar to rare diseases, sepsis is a little-known and often misunderstood condition among patients—many of whom do not understand the high risk that sepsis poses.

“Sepsis is very, very common—and ostensibly, we have treatments,” Heymann began. “Although, with antimicrobial resistance (AMR), those treatments are disappearing, and we’re seeing more and more folks who need a second or third or fourth, even different treatment to successfully treat infections.”

Awareness of sepsis is growing, but still low

“Many people think sepsis is rare,” explained Heymann. “In 2002, only 19% of the country had heard the word before. And half or more couldn’t tell you what it was. And amazingly, Microsoft Word did not even have the word in its dictionary, so sepsis was a spell-check error 20 years ago. We’ve come a long way from those statistics.”

By 2022, Sepsis Alliance found that “66% of U.S. adults were aware of the term sepsis yet only 19% of them could correctly identify all four of the most common sepsis symptoms.” Often, people think sepsis is a type of infection, but that is not the case.

“It’s our body’s response to an infection that can damage our vital organs and very often causes death,” he explained.

Much like getting stung by a bee, it is not the bee sting that kills; it’s the body’s reaction to the bee sting that can prove deadly. “Similarly with sepsis, any type of infection—bacterial, viral, parasitic, or fungal—can set off that cascade to sepsis, which is common, deadly, and expensive,” Heymann said.

The toll of sepsis in the U.S.

“There are 1.7 million cases of sepsis each year in the U.S., and we believe that’s an undercount,” Heymann said, noting that inflammatory infections like COVID are contributing to the rise in sepsis cases. “The mortality rate is extremely high: 350,000 adult deaths each year in the U.S., 11 million globally. It’s responsible for the deaths of nearly 7,000 children in the U.S. each year, which is more than cancer, as well as for over one in three hospital deaths.”

For the immunocompromised, the risk is higher. “If you have an immune compromising condition, or if you’re taking immunosuppressing drugs for your illness, these may increase your risk of developing an infection and having a weaker-than-what-would-be-hoped-for immune response to fight that infection,” Heymann said.

“When one in three people dying are dying related to sepsis, it’s not surprising that it’s the number one cost of hospital care in the country,” Heymann pointed out. “Readmissions are a problem. 40% of survivors are back in the hospital within 90 days. So it’s not really being settled or resolved, and there’s actually kind of an ongoing chronic component to sepsis, with more than half of survivors having ongoing challenges.”

“More than three-quarters (77%) of respondents missed at least one month of work, with more than one-third (34%) missing at least a year,” another Sepsis Alliance survey of survivors found. “Many sepsis survivors experience post-sepsis syndrome, a condition that includes physical and/or psychological long-term effects. More than 80% of respondents reported ongoing mental, cognitive, or physical challenges following sepsis, with more than 30% indicating the severity to be extreme,” all of which contributed to their inability to return to work.

“So there’s a huge workplace productivity issue,” Heymann said. “There’s a huge mortality risk and lots of morbidity issues—including 14,000 amputations each year. Very often, it’s labeled as complications of something else.”

How Sepsis Alliance is advocating for change

Patient advocacy groups are doing a number of things to combat sepsis.

“There’s a tremendous amount of heterogeneity in sepsis. We’re finding that we may be going down a path with sepsis that looks more like cancer than a specific disease,” Heymann said. “And for that reason, we’re moving as fast as we can toward creating an infrastructure for a national sepsis registry, like the cancer registries that have been so helpful in understanding the heterogeneity that exists within cancer.”

“I think the lack of that knowledge, and that access to the patient data is holding us back from really being able to refine the research, refine the diagnostic process, refine the therapies, so that we can actually do a better job at treating folks who have sepsis, and so we can reduce the mortality, which is very, very high,” he continued.

Sepsis Alliance is talking to voters and bringing those conversations to politicians and policymakers.

In a survey of registered voters late last year about AMR and sepsis, “only about half are actually familiar with the terms,” noted Heymann. “But once they were aided to understand it and what it meant, the issue really resonated with folks. 70% referred to it then as a major problem that was getting worse, and it was bipartisan.”

Policy solutions to slow the spread of AMR

The Sepsis Alliance coupled education about sepsis and AMR with advocacy for legislation under consideration in Congress. “Similarly, with the PASTEUR Act, there was very low familiarity, about 18% being familiar with it, but then, once aided about what it would do, it got 90% support from respondents—again, it was bipartisan,” said Heymann.

The final step is translating grassroots conversations to the politicians working to best serve their constituents. “This kind of information, I think, can really help equip us when we go to speak to elected officials and when our advocates go to speak to elected officials. These are your constituents who care about this issue or are being impacted by the issue. They want you to do something about it.”

“Working together is obviously so, so powerful because we share these patients and their vulnerabilities. These are real people. These elected officials see reports of these real people, and they recognize those people within themselves.”

To learn more, sign up here for Sepsis Alliance’s healthcare professional mailing list. Check out EndSuperbugs.org for more information about AMR and sepsis. And mark your calendar for the Sepsis Alliance AMR Conference on April 30, 2025!