One in eight global deaths in 2019 was caused by common bacterial infections, which are the second leading cause of death worldwide, right after ischaemic heart disease, according to a study providing the first global estimate of the lethality of these infections, published in The Lancet last month.

The comprehensive study was published by the Global Research on Antimicrobial Resistance (GRAM) Project, a partnership between the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) and the University of Oxford.

The study was done using methods from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019, a vast research program funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, in addition to “a subset of the input data described in the Global Burden of Antimicrobial Resistance 2019 study.”

Full toll of bacterial infection

According to data published in the Lancet, an estimated 7.7 million people died in 2019 due to common bacterial infections with cases associated with the 33 bacterial pathogens—both antibiotic-resistant and non-resistant—“comprising 13.6% of all global deaths and 56.2% of all sepsis-related deaths in 2019.”

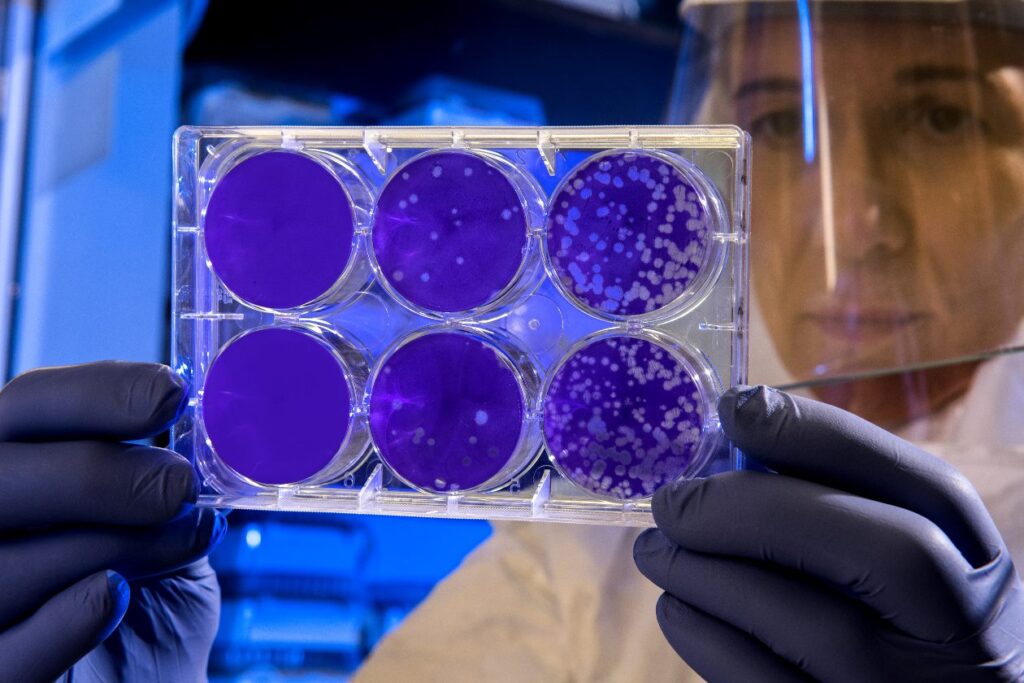

Only five of these 33 pathogens—Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa—”were responsible for 54.9% of deaths among the investigated bacteria,” the study showed.

“These new data for the first time reveal the full extent of the global public health challenge posed by bacterial infections,” said Dr. Christopher Murray, study co-author and Director of the IHME at the University of Washington’s School of Medicine. He emphasized that it is of utmost importance “to put these results on the radar of global health initiatives … so proper investments are made to slash the number of deaths and infections.”

Stark differences between poor and wealthy regions

As the study points out, “the age-standardized mortality rate linked to the 33 pathogens varied by super-region in 2019” is “highest in sub-Saharan Africa, at 230 deaths per 100 000 population,” but it’s significantly lower in the wealthiest parts of the world, with 52·2 deaths per 100 000 population.

“Iceland had the lowest rate, with 35.7 deaths per 100 000 population in 2019” whereas the Central African Republic was the country with the highest age-standardized mortality rate, with 394 deaths per 100 000 population.

According to The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, “Australia’s mortality rate per 100,000 residents is placed between 35 and 50,” with the analysis citing “Staphylococcus aureus as the pathogen causing the highest mortality (10.1 deaths per 100,000 people), followed by Escherichia coli (6) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (3.5).”

Insufficient funding

The study also analyzed the funding levels for infectious disease research, finding that investment into tackling bacterial infections lagged substantially.

Although bacterial infections caused significantly more deaths, researchers established that “they receive comparatively little public health attention relative to their burden, and minimal research funding relative to other diseases with a comparable, or lower, burden.”

Data shows that there was $1.4 billion for Staphylococcus aureus and $800 million for Escherichia coli research compared to $42 billion in funding for HIV research between 2000 and 2017, even though there were 864,000 global deaths linked to HIV/AIDS in 2019, which equaled to around 11% of those linked to bacterial infection over the same period, as RCGP article pointed out.

As Bio.News has reported, the market for antimicrobials, including those that fight bacterial infection, is not set up to support research and development.

Noting that “this study will be useful for the development of targeted strategies to reduce the high bacterial disease burden in the worst affected countries,” Prof Christiane Dolecek, a lead researcher for the GRAM study at the University of Oxford, said that “this evidence should serve as a call to arms for global vaccine developers to enhance and expedite the development and implementation of new vaccines for priority bacterial pathogens for which a vaccine is not currently available.”