Eleven years after the first CRISPR patent was filed, we’re anticipating what could be the first approval of a gene therapy based on CRISPR: exa-cel, a treatment for sickle cell disease (SCD) and beta thalassemia developed by CRISPR Therapeutics and Vertex Pharmaceuticals.

What’s most exciting about CRISPR is the ability to address “unmet need,” particularly for diseases “often overlooked by the medical community,” said Julianne Bruno, VP and Head of Program Management for CRISPR Therapeutics, speaking at the BIO CEO and Investor Conference on Tuesday.

Currently, not a lot can be done for patients with SCD and beta-thalassemia, said Bruno. But exa-cel could be a “one-time, functional, durable cure.”

To date, 75 patients have been treated, and some have followed up out to three years. The companies completed their filings in Europe and the U.K., which have been validated; the rolling submission in the U.S. is ongoing, with completion targeted for the end of the first quarter of 2023.

“CRISPR is at the front of a new, pioneering landscape for gene editing,” she said. However, the “regulatory picture is changing daily,” which is why the companies have “frequent contact” with the FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA).

The next wave: in vivo gene editing

Silvan Tuerkcan, Ph.D., of JMP Securities, led the fascinating discussion with Bruno and two additional CRISPR innovators about what’s next for the technology and the world-changing breakthroughs that might be here sooner than you’d think.

One development waiting in the wings: in vivo gene therapy, said David Baram, Ph.D., President and CEO of Emendo Biotherapeutics, which is working to make gene editing even more precise.

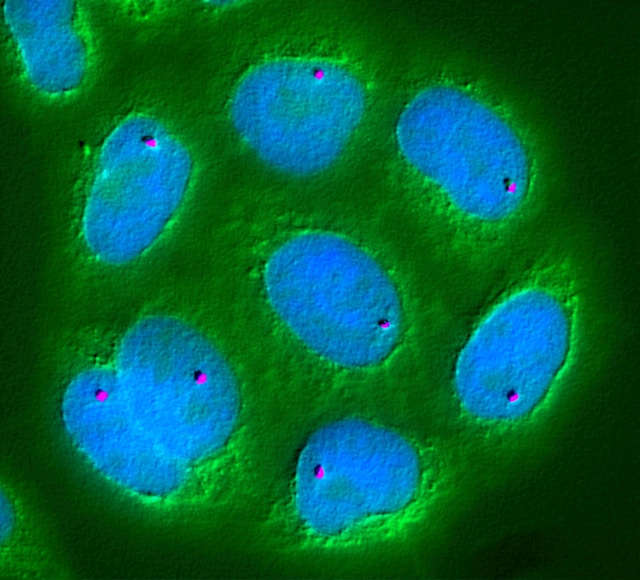

Ex vivo gene therapy, which is most commonly studied, “takes cells from your body, modifies them in a lab, and puts them back into the body,” explains GoodRx Health. For example, exa-cel is an “ex vivo CRISPR/Cas9 gene-edited therapy in which a patient’s own hematopoietic stem cells are edited to produce high levels of fetal hemoglobin (HbF; hemoglobin F) in red blood cells,” says BioSpace.

In vivo, on the other hand, “uses viruses or other methods to deliver genes directly into your cells,” says GoodRx Health. Verve Therapeutics, for example, is studying in vivo gene therapy to treat cardiovascular disease, with trials underway in New Zealand and the U.K.; the FDA placed a hold on the U.S. study until more data is available.

If in vivo can reach the clinic, it would be a “major milestone for the entire industry,” Baram told Tuesday’s panel. Emendo plans to start trials outside the U.S. to generate sufficient data that will allow them to have a trial in the U.S.

The CRISPR era is here

“CRISPR is the sea change with therapeutics,” said Benjamin L. Oakes, Ph.D., Co-Founder, President, and CEO of Scribe Therapeutics, which is developing next-gen CRISPR technology. While much of the narrative has been about the impact of CRISPR on rare diseases, Oakes thinks we’ll see the use of CRISPR in less rare diseases, too—sooner rather than later.

Specifically, we could be looking at a world in which “50% of the most prevalent disease,” such as cancer and cardiovascular disease, could be treated or eliminated with gene therapy, echoed Bruno.

Baram agreed we’ll quickly move into applications for highly prevalent diseases and conditions, and in 25 years (or sooner), discussions will be about prevention.

“We’re very good at knocking out genes. We’re improving in correcting genes,” he told Bio.News in an interview after the panel. “And then we’ll get to a point where we can actually correct genes and [take out] known mutations that significantly increase the risk for certain diseases.”

“As technology evolves, this stage will be unstoppable—because it will make sense,” he said. “Why don’t you just make someone healthier?”

While COVID-19 will earn a place on the era’s medical timeline, above all, “this 100-year span,” said Oakes, will be known as the era in which “we learned how to modify the genome.”

CRISPR leads to discussions about moral issues, access

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eELvxgikV7A[/embedyt]

Of course, these developments will lead to “moral discussions,” explained Baram. “What is the extent that you can make human beings better?… What does it mean to have people live longer?… Is it accessible to everyone? What does this mean that we can make certain people that can pay for that generally healthier?” Baram said in the interview.

“It’s a different level of access to health care. And this is, again, a very significant moral discussion that exists today and will have to be solved in a different way since we’re talking about manipulating people’s genes.”

Then, there is the persistent narrative in the media and among payers that gene therapy is too expensive.

“Pricing is an issue, but it has to make sense,” Baram told us, noting that price is a component of Emendo’s five-year and 10-year plans.

“It is very fair and needed to demand from companies to get the prices down and to make them as low as possible,” he said. “At the same time, it has to be realistic. You don’t want to get a sale to be so low that you lose innovation—that you lose the ability to cure people.”

“How do you price a cure?” he asked, especially when you factor in “how much it costs to treat this patient with medication and everything else along the lifespan…and add to that the significant improvements in quality of life that a cure provides.”

All players need to work on this issue, including improving the cost of production. “At the same time, payers will have to realize that this is something different than what they have seen before. Because now we’re pricing a cure. We’re potentially pricing the transformation of a patient from being sick to being healthy. How do you price that?”