For three decades, Genethon, a non-profit research organization, has pioneered development of gene therapies for rare and ultra-rare diseases. Now that our hard work is demonstrating clinical success, we face an even greater challenge: ensuring our patients, primarily children, benefit from these life-saving medicines.

For several years, our scientists have been developing a successful gene therapy for Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome (WAS), an ultra-rare disease that affects between 1 and 10 males per million worldwide. This year, we are conducting a pivotal trial of a gene therapy for Crigler-Najjar syndrome, a similarly ultra-rare condition that affects about 1 person (male or female) per 750,000 to 1 million people worldwide.

Both treatments represent first-ever gene therapies for these patients whose inherited genetic diseases are usually diagnosed soon after birth and can be deadly. However, at present we have no way to provide these treatments to all patients, making celebrations frustrating for our dedicated scientists and the heroic families and their children who serve as research subjects.

The dilemma epitomizes what Genethon and other proponents of gene and cell therapies have identified as the lack of interest in these pathologies by pharma or biotechs, which would rather focus on more profitable indications with larger patient populations.

When you add to this exasperation the lack of adequate public and private funding it translates into a maddening irony. Some 300 million people worldwide who suffer from one of more than 7,000 rare diseases may never gain access to new therapies. Two-thirds of these diseases afflict children, and the vast majority have no relief. Ninety-five percent of rare diseases lack appropriate treatment and 85% of these are considered too rare for private industry investment in clinical development and commercialization.

Our WAS and Crigler-Najjar gene therapies provide an instructive case in point.

How can we ensure patient access to rare disease therapies?

WAS is caused by a mutation in the WAS gene in hematopoietic cells resulting in hemorrhages, severe infections, severe eczema, and, in some patients, cancers. The only treatment currently available is bone marrow transplantation, which requires a compatible donor and can cause serious complications.

Crigler-Najjar is a liver disease characterized by abnormally high levels of bilirubin in the blood (hyperbilirubinemia). It is caused by a deficiency of the UGT1A1 enzyme, responsible for transforming bilirubin into a substance for elimination by the body. High levels of bilirubin can result in neurological damage and death if not treated quickly. At present, patients undergo phototherapy for up to 12 hours a day to keep bilirubin levels below the toxicity threshold.

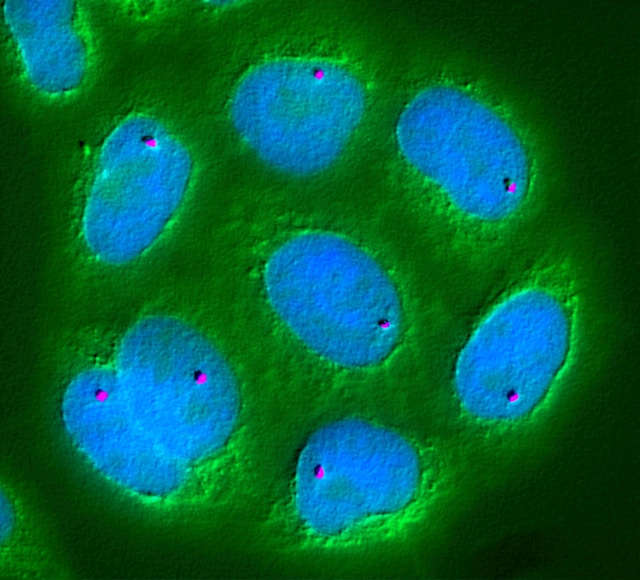

Our WAS gene therapy involves extracting from patients the blood stem cells carrying the genetic abnormality, correcting them in the laboratory with a healthy WAS gene—which is delivered with a lentiviral vector—and transplanting the cells back into the patients.

The Crigler-Najjar gene therapy combines normal copies of the UGT1A1 gene coding for the bilirubin metabolizing enzyme with an AAV vector and is administered intravenously.

Despite these remarkable achievements, we struggle with how to make these life-saving therapies available to patients who live in many countries.

If we had standardized clinical development regulations, specifically adapted to the rarity of these pathologies, and if we had enough funding, we could partner with hospitals, open clinical trials in places with a significant concentration of patients, and treat them on a compassionate-use basis.

Because most rare disease patient populations are too small, existing government incentives in the U.S. and Europe are not sufficient for biopharmaceutical companies to invest in development and commercialization. A new kind of economic model will be required if patients are to receive the care we owe them.

Genethon joined the Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium in the U.S., which brings together private and public actors, to address these challenges, and we are hopeful it will have an impact.

But unless similar initiatives are coordinated at the international level, milestones such as our WAS and Crigler-Najjar gene therapies may end up being a cautionary tale about our failure to deliver the cures for patients who desperately need them.

Frederic Revah, Ph.D., is Chief Executive Officer of Genethon.