In recent years, the number of disruptive, cutting-edge therapies approved or under review by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has grown substantially. So-called transformative therapies, including cell and gene therapies, offer new treatment options for patients, often for conditions that currently have limited or no treatment options available.

However, these therapies also present challenges related to payment and access that vary by payer market and setting of care. Because they are characterized by having a small patient population; often no existing highly effective treatment; a substantial “cure” rate; and high cost; many transformative therapies do not fit neatly into legacy payment systems that often discourage the use of new technologies and may not pay accurately for low patient populations.

In response, a number of “outside-the-box” solutions for transformative therapy payment and coverage have begun to emerge.

New ways of financing will be necessary across all manner of payers. In 2023, Avalere Health estimated in a report for the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) that 35% of the transformative therapy pipeline will have Medicaid/CHIP as a primary payer and that more than two-thirds of the transformative therapy pipeline will have some government-sponsored insurance as a primary payer. This compares with the overall coverage for the U.S. population of more than 50% for commercial insurance and about 20% for Medicare and Medicaid.

The potential for a higher percentage of patients with government-sponsored insurance to be treated by transformative therapies raises important considerations for state and federal budget impact of the growing transformative therapy pipeline.

Innovative payment arrangements

As the numbers show, the vast unmet medical need exhibited by the patient population in Medicaid, along with the limited budgets many states face to serve them, has made state Medicaid programs a natural place to launch innovative payment arrangements.

“Innovation needs to not just happen on the laboratory research bench, it needs to happen throughout all drug delivery phases, and that includes reimbursement and payment,” according to Jack Geisser, Senior Director, Healthcare Policy, Medicaid, and State Initiatives at BIO. “There need to be different ways to ensure that cash-strapped Medicaid programs can provide access to the latest treatments.”

The proposed Medicaid VBPs for Patients (MVP) Act, and state-level legislation that’s already been passed, offer innovative approaches to enable new means of payment that increase patient access to the latest treatments.

BIO has expressed support for the MVP Act, and value-based payment agreements in general. As Geisser explains, there are several creative arrangements that can help increase patient access by focusing on the true value of medication.

That’s the idea behind innovative payment arrangements—agreements between drug makers and Medicaid officials to increase access to transformative new therapies whereby manufacturers and states share risk, fully reimbursing manufacturers for the most effective treatments and enabling longer-term payment schedules.

Payments for curative single-dose treatments

Revolutionary drugs offering the potential to cure or dramatically improve the health of patients include cell and gene therapies, as well as “a whole variety of transformational treatments that are really providing innovation in the marketplace,” according to Geisser.

These drugs offer value over time by improving patients’ health dramatically with a single course of treatment. But the challenge with paying for these treatments is that states have Medicaid budgets that last one or, at most, two years. Proposals to allow states to spread out the payments for an expensive curative single-course treatment are designed to increase access to cutting-edge therapies while providing more predictable budget sequencing in the long term.

Examples of these treatments include the first cell-based gene therapies for sickle cell disease (SCD), Casgevy by Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and Lyfgenia by bluebird bio. These inpatient treatments have high upfront costs but can potentially cure the disease.

While the new SCD treatments can cost around $2 million, lifetime costs for medical treatment of someone with severe SCD have been estimated at $5.2 million. In addition, patients can suffer premature death, unbearable pain, and loss of work due to their condition.

Other highly effective single-dose treatments that can benefit from innovative payment schemes include direct acting antiviral (DAA) drugs, which can cure hepatitis C and are administered in simple tablet form. DAA treatments can cost around $20,000 for a full course and insurance coverage is limited, which is apparently driving what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) describes as disappointing uptake.

“There’s been a lot of activity around providing those treatments through innovative payment arrangements because a large share of hepatitis C patients are on Medicaid, so states with high numbers of those patients are thinking about how best they can provide those treatments,” says Geisser.

Payments based on milestones of success

Another innovative approach to increase patient access involves value- or outcomes-based payment agreements, whereby drug manufacturers share risk based on the effectiveness of a treatment, thereby ensuring states are paying for the value the treatment provides.

A treatment’s effectiveness can be determined through metrics such as reduced hospitalizations, or for example in the case of an epileptic drug, fewer seizures. If the drug does not meet—or stops meeting–these milestones for a patient, the manufacturer who negotiated the agreement would provide a larger rebate.

“Not every drug works the same for every patient. One may work well for 90% of the cases, but in 10% of patients you may meet some of the metrics but not all,” says Geisser. In cases where some targets for outcomes are not met, the manufacturer would give the larger percentage of rebate back to the state, he explained.

These voluntary value-based payment arrangements can enable states to cover newer treatments, increasing access for all patients. The arrangements often involve complex negotiations, which must be concluded between state officials and drug makers.

Under long-existing Medicaid payment rules, if a value-based payment arrangement adjusts payment for a drug based on success rates, and a drug does not work for one patient, necessitating a larger rebate, that would trigger a lower Medicaid “best price” sending distortionary ripples across the existing payment system. To prevent individual outcomes from skewing the price of a drug, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) now uses a “multiple best price rule,” which permits more realistic price reporting for drugs under VBAs and for those not subject to a VBA.

In another way to facilitate innovative payment arrangements, many states now negotiate voluntary innovative outcomes-based arrangements as supplemental rebates.

Legislation and regulation

While the regulatory “multiple best price rule” helps enable payment agreements, drug makers and BIO have stressed the need to codify these rules in legislation, to ensure that agreements are durable and will continue to enable greater patient access.

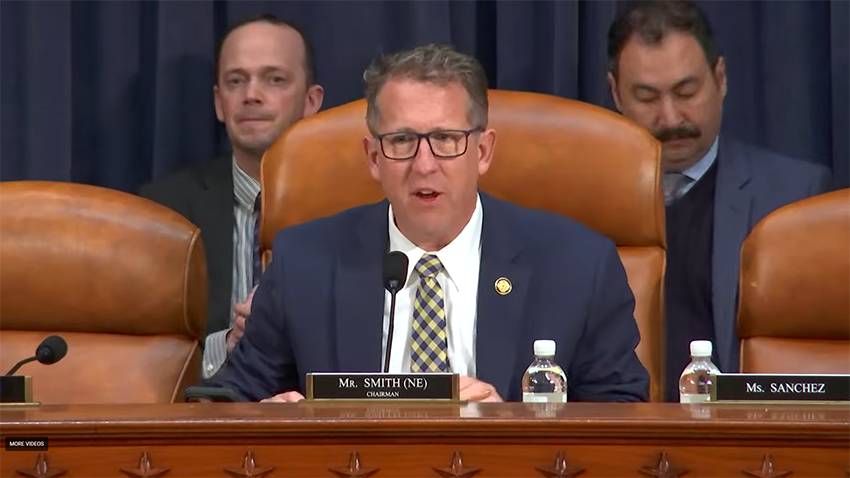

One such bill to secure value-based payment agreement options is the Medicaid VBPs for Patients (MVP) Act, put forth by House Energy and Commerce Health Subcommittee Chair Brett Guthrie (R-KY) and Ranking Member Anna G. Eshoo (D-CA), with Reps. John Joyce, M.D. (R-PA), Jake Auchincloss (D-MA), Mariannette Miller-Meeks (R-IA), Scott Peters (D-CA), and others.

“The Medicaid VBPs for Patients Act would help get life-saving treatments to the most vulnerable patients across the country. With the flexibility this legislation provides, states can make high-cost therapies and cures for rare diseases available without raising taxes or cutting other state programs,” according to a statement from Rep. Guthrie.

BIO also supports legislation introduced in several state legislatures and already passed in some, that would give Medicaid programs and manufacturers the ability to enter into voluntary value-based agreements under supplemental rebate agreement auspices. This legislation gives states the flexibility to either accept agreements that are negotiated under the multiple best price rule—which would require them to possibly accept agreements that have been negotiated with other states—or to negotiate their own value-based agreements under a supplemental rebate agreement that is tailored to the needs of their own state’s population.

Moreover, a new demonstration model from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) under CMS seeks to foster greater use of value-based agreements for cell and gene therapies. It is beginning with sickle cell disease (SCD), for which the two new gene therapies were recently approved but may move beyond that disease state. CMMI intends to be a primary negotiator for new value-based agreements as supplemental rebates for SCD treatments to streamline the negotiation process. Much like the multiple best price rule, the one agreement that CMMI negotiates would be available to all state Medicaid programs.

‘Not a panacea’

While value-based payment agreements will do a lot to increase access to medicines, “they are not necessarily a panacea,” Geisser notes.

“For some diseases, there are just too many endpoints, or clinical factors for patients to determine whether a given metric can indicate whether ‘this drug is working or not working,’ ” says Geisser. For example, a very small patient population or patient frailty could make such measurement extremely difficult, or there could be other factors that make it difficult to measure success. It may mean some other type of innovative contract might be better, but room should be left for innovation.

In an ideal situation, treatments will work as intended for most or all patients, and drug makers will pay minimum rebates, meaning state Medicaid programs will pay the full amount for treatments. But that’s a good thing for patients, Geisser notes.

“When treatments work well, the money that the payer will save is not necessarily on the pharmaceutical side. It’s saving money in the value on the treatment side, on the larger healthcare expenses that a patient might have, what we call the spillover effect,” Geisser says. “Nevertheless, we believe strongly that these agreements are going to get patients the drugs they need faster and improve access and the quality of health overall.”