June 19 is World Sickle Cell Day, a day to highlight the work needed to address sickle cell disease (SCD) as well as the significant disparities in healthcare in the U.S.

Here’s what you need to know.

What is sickle cell disease?

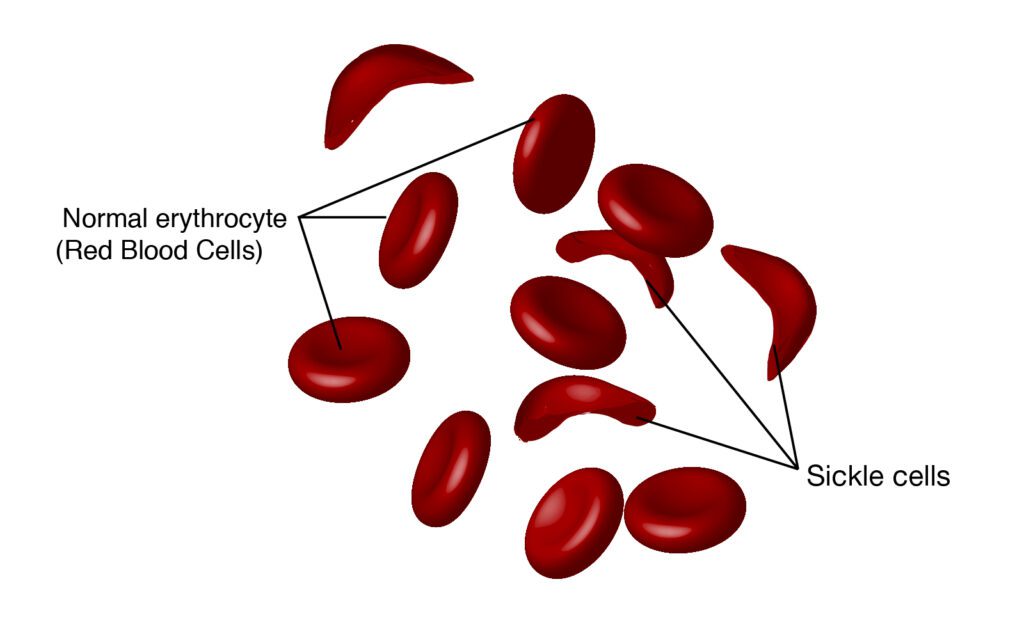

SCD is a genetic blood disorder that affects the shape and function of red blood cells.

For patients with SCD, red blood cells lose their usual round shape and become crescent-shaped. These abnormal cells can block blood vessels, causing reduced blood flow and oxygen delivery. This leads to various health issues including pain, fatigue, organ damage, and a higher risk of infections.

Not only does SCD cause debilitating life circumstances, but in the U.S., it also largely affects historically marginalized communities in the U.S. and globally. An estimated 100,000 Americans live with SCD, and it occurs in about 1 out of every 365 Black or African American births, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Globally, SCD is most common in sub-Saharan Africa, where about 236,000 babies are born with SCD each year – more than 80 times as many as in the U.S. As many as 90% of those babies will die during childhood, according to the New England Journal of Medicine.

The history of SCD treatments

SCD was discovered in the U.S. in 1910 but took until 1960 for the use of blood transfusions to be considered a treatment. However, blood transfusions were unsuccessful in curing the disease.

Then, in 1972 Congress passed the National Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act, which ensured the education, research, and treatment of SCD.

Later, in 1984, stem-cell transplants were used as a method of treatment and became the first curative therapy. The problem is that fewer than 20% of SCD patients have a donor match.

In the 1990s, the first medication treatment was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA): hydroxyurea. It was originally a drug used to slow the spread of cancer but was proven to prevent the formation of sickle-shaped cells. Throughout the 2000s various other drugs were approved by the FDA, but the research still remained minimal.

What are recent SCD discoveries?

In 2019, gene editing was employed to prevent the development of SCD. The trials were to assess long-term effects on the body and were in a state of waiting for a few years.

In 2020, Global Blood Therapeutics (GBT), a member of the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO), released Oxbryta, the first drug that attacks the underlying cause of sickle cell disease.

Oxbryta binds directly to hemoglobin S, allowing oxygen affinity to normalize and inhibit polymerization, which leads to normal formation of blood cells.

In 2022, GBT released two new treatments undergoing clinical trials, inclacumab and GBT021601 (GBT601). Both were granted orphan drug and rare pediatric disease designations by the FDA

GBT reported: “Inclacumab is a novel, fully human monoclonal antibody that selectively targets P-selectin, a protein that mediates cell adhesion and is clinically validated to reduce pain due to VOCs (vaso-occlusive crises) in people with SCD. Preclinical results suggest that inclacumab has the potential to be a best-in-class option for reducing VOCs in people with SCD, with the potential for quarterly, rather than monthly dosing.”

As of 2023, Inclacumab is in its final stages of clinical trials and reportedly has a high likelihood of being approved by the FDA.

The company also released that GBT601 “is a next-generation sickle hemoglobin (HbS) polymerization inhibitor,” GBT601 is still in phase 1 trials as of 2022.

And new developments could be here soon.

On June 8, 2023, Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated and CRISPR Therapeutics announced the FDA has accepted their application for a new gene editing treatment for severe SCD.

Vertex is an American biopharmaceutical company dedicated to the discovery of new bio-based treatments.

CRISPR Therapeutics is a Swiss-American company that focuses on gene-editing treatments.

Their new treatment, exa-cel, is being developed as a potential treatment for SCD and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia (TDT), a disease where individuals require lifelong regular red blood cell transfusions to survive.

According to CRISPR Therapeutics, “A patient’s own hematopoietic stem cells are edited to produce high levels of fetal hemoglobin (HbF; hemoglobin F) in red blood cells. HbF is the form of the oxygen-carrying hemoglobin that is naturally present during fetal development, which then switches to the adult form of hemoglobin after birth. The elevation of HbF by exa-cel has the potential to reduce or eliminate painful and debilitating VOCs for patients with SCD and alleviate transfusion requirements for patients with TDT.”

The FDA has given priority status to the application to use exa-cel for SCD. The application for exa-cel use against TDT will undergo a standard review process. The FDA has set target dates for making decisions on these applications: December 8, 2023 for SCD, and March 30, 2024 for TDT.

Reshma Kewalramani, M.D., Chief Executive Officer and President of Vertex, stated: “We are very pleased with the acceptance of the submissions and the Priority Review designation for SCD by the FDA, as well as the progress of the exa-cel filings in the EU and U.K.. Exa-cel holds the promise to be the first CRISPR gene-editing therapy to be approved, and we continue to work with urgency to bring this treatment with transformative potential to patients who are waiting.”

SCD ‘epitomizes inequity’

Dr. Ted Love, the newly elected Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) Board Chair, was President and CEO of Global Blood Therapeutics (GBT), a company dedicated to the discovery of new cures for SCD and other blood diseases.

In a past conversation between Dr. Love and BIO, he stated: “Sickle cell disease epitomizes healthcare inequity. It’s a genetic disease. It resides primarily in African Americans because the disease was primarily in areas where malaria was endemic. And of course, there’s no malaria in the U.S. The way the gene got into the U.S. is through slave importation from areas where malaria was endemic. We’ve had gene pool mixing, so there are white people with sickle cell disease—but it’s still largely in the Black community.”

There has long been a disparity in the “lack of investment in research funding,” he continued. For example, in 2011, cystic fibrosis received about 440 times as much national foundation research funding per patient, and federal and private funding disparities have continued.

To learn more about sickle cell disease, listen to the sickle cell episode of the I am BIO Podcast, which featured GBT’s Dr. Ted Love and Mapillar Dahn, Founder of the My Three Sicklers Sickle Cell Foundation, who has three daughters born with the disease.